Computational Analysis of Social Complexity

Fall 2025, Spencer Lyon

Prerequisites

- Julia setup

- Julia basics

- Julia types and methods

Outcomes

- Understand key components of networks/graphs

- Use the Graphs.jl package for working with graphs in Julia

- Implement the breadth-first search algorithm

References

- Easley and Kleinberg chapter 2

Introduction¶

Why Study Graphs?¶

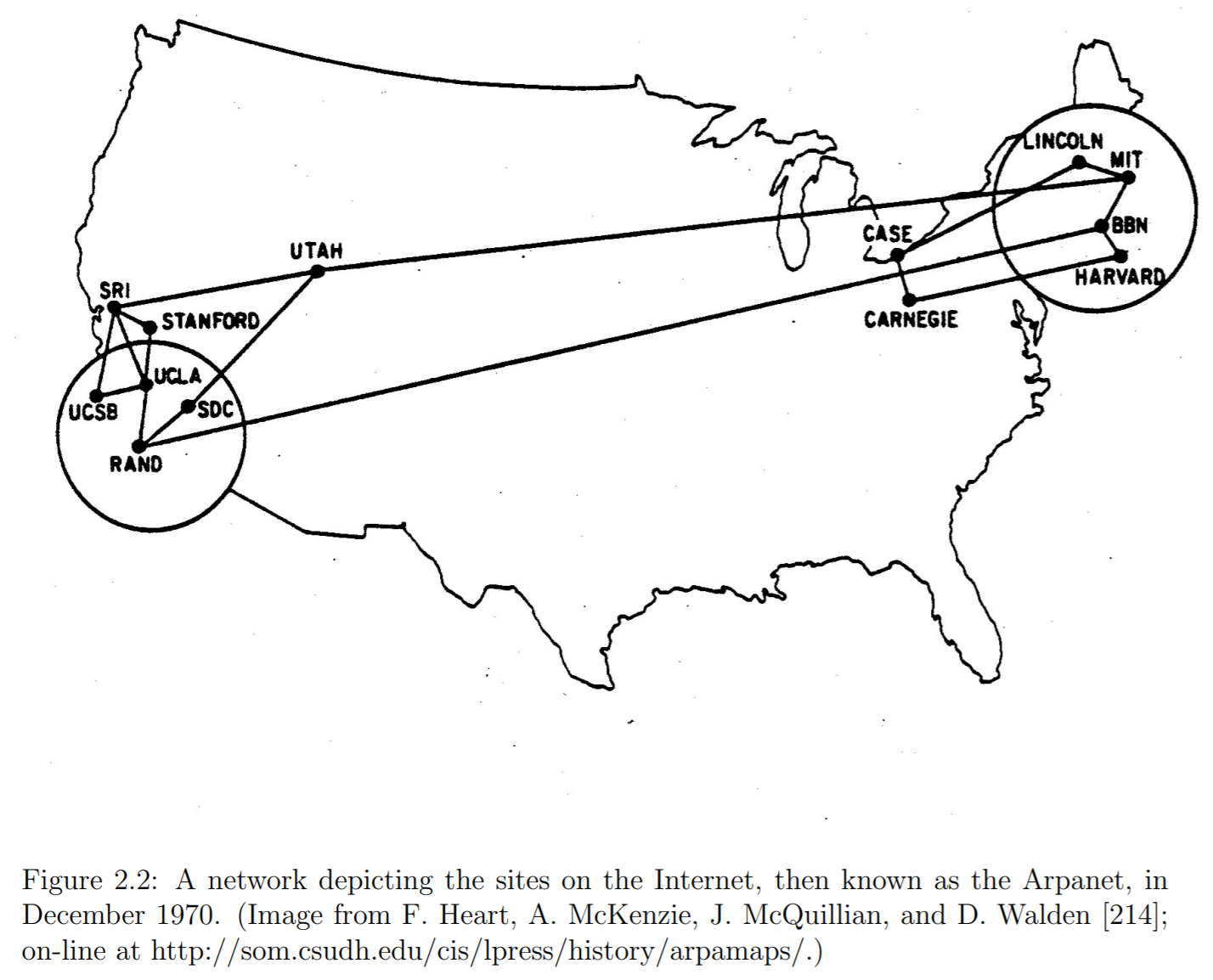

- Economic, cultural, political, and social interactions are influenced by structure of relationships

- Transmission of viruses

- International trade, supply chains, marketplaces

- Spread of information, diffusion of innovation

- Political persuasion, localized voting patterns

- Human behaviors influenced by network of friends (sports, clothes, music)

- Behaviors can be effected by social networks

- “Influencers”

- Circles of followers can create echo chambers

Edges and Nodes¶

- A graph specifies relationships between a collection of items

- Each item is called a node

- A relationship between nodes is represented by an edge

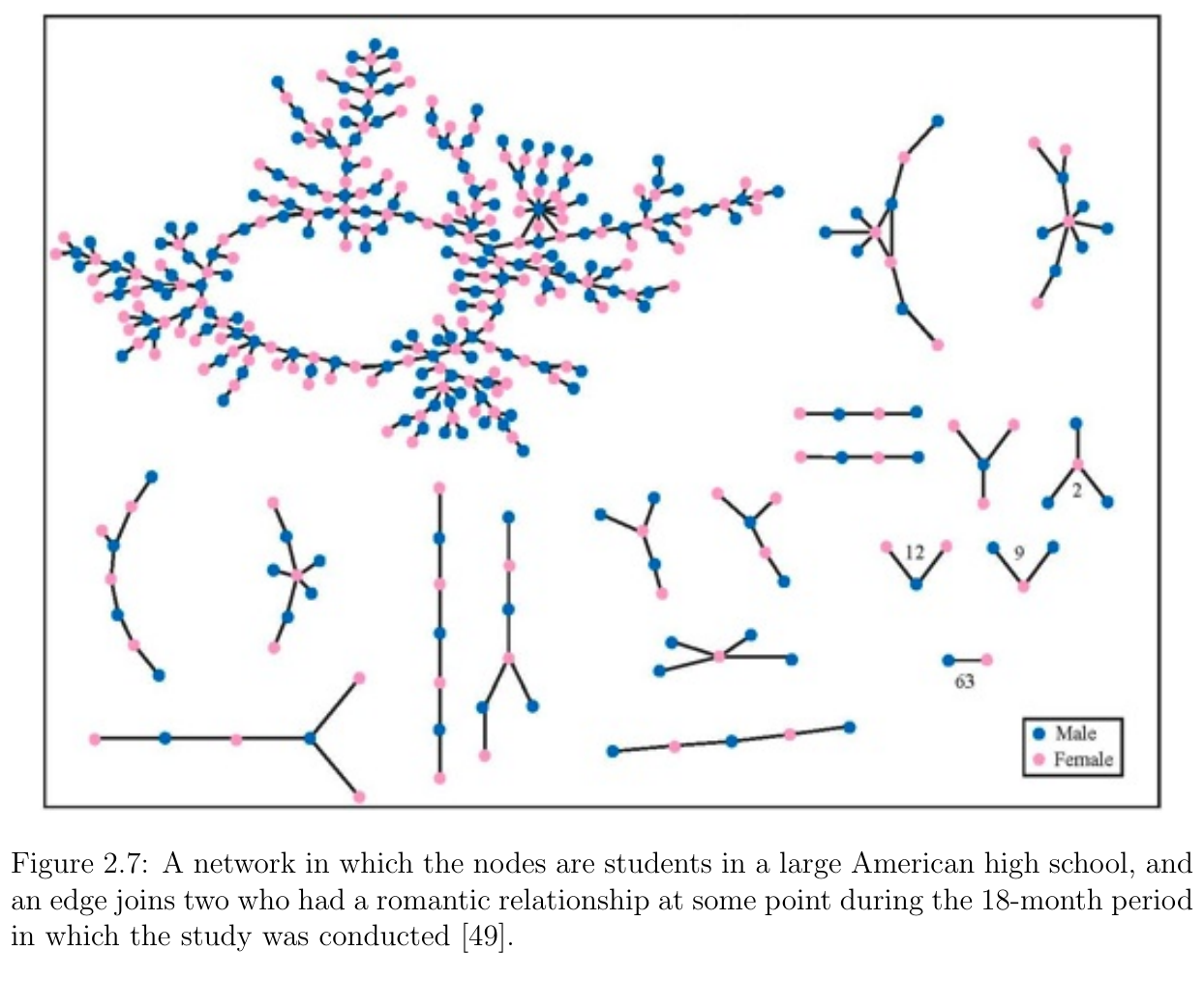

- Visually, graphs might look like this:

- Here the nodes are

A,B,C,D - The edges connect nodes

A-B,B-C,B-D,C-D

Adjacency Matrix¶

- How might we represent the graph above numerically?

- One very common approach is to use a matrix of 0’s and 1’s called an adjancency matrix

- Suppose we have a graph of nodes

- Without loss of generality, we’ll represent them as integers

1:N

- Without loss of generality, we’ll represent them as integers

- Let be our adjacency matrix

- Element will be zero unless there is an edge between nodes and (diagonal is left as 0)

- In our above we had

- Nodes

A,B,C,D(or 1, 2, 3, 4 respectively) - Edges connecting nodes

1-2,2-3,2-4,3-4

- Nodes

- The adjacency matrix for this example is

Graphs in Julia¶

- In Julia there are a few ways we could represent our example graph above

- We could start with the adjacency matrix concept as follows

A = [

0 1 0 0

1 0 1 1

0 1 0 1

0 1 1 0

]4×4 Matrix{Int64}:

0 1 0 0

1 0 1 1

0 1 0 1

0 1 1 0Working with Adjacency Matrices¶

- An adjacency matrix gives us a lot of information about the structure of the graph

- We could compute all of the following

- Total number of nodes: number of rows or columns of

- Total number of edges:

- Node with most edges:

- Average number of edges per node:

Exercise: Adjacency Matrix¶

- In the cell below we have defined an adjacency matrix called

A_ex1 - Using

A_ex1answer the following questions:- How many nodes are in the graph?

- How many edges?

- Node with most edges (hint, use the

dimsargument tosumand then theargmaxfunction) - Average number of edges per node

- Number of connections for node 7:

import Random

Random.seed!(42)

A_ex1 = zeros(Int, 30, 30)

for i in 1:30

for j in (i+1):30

if rand() < 0.2

A_ex1[i, j] = 1

A_ex1[j, i] = 1

end

end

end# Your code here

ex1_total_nodes = missing

ex1_total_edges = missing

ex1_node_most_edges = missing

ex1_average_edges_per_node = missing

ex1_connections_node_7 = missingmissingGraphs.jl¶

- There are many smart graph theory experts in the Juila community

- They have built a package called Graphs for working with graphs (as well as ancillary pacakges for extra features)

- We can build a

Graphs.Graphobject directly from our adjacency matrix

using GraphsG1 = Graph(A){4, 4} undirected simple Int64 graphcollect(edges(G1)) # collect turns an `iterator` into an array4-element Vector{Graphs.SimpleGraphs.SimpleEdge{Int64}}:

Edge 1 => 2

Edge 2 => 3

Edge 2 => 4

Edge 3 => 4collect(vertices(G1)) # Graphs refers to nodes as `vertices`4-element Vector{Int64}:

1

2

3

4Visualizing Graphs¶

- We can use the GraphPlot package to visualize our graph

- Note that the actual placement of the nodes is randomly generated and then tweaked to clearly show all nodes and edges

- The important thing is not the placement of nodes, but rather their relative structure

using GraphPlot # load GraphPlot packagegplot(G1)Loading...

Size considerations¶

- Using

Array{Int64,2}to store an adjacency matrix turns out to be a rather costly way to store a graph - In the original example graph we had 4 nodes and 4 edges

- To store this we needed to have a 4x4 matrix of 64 bit integers

- This is only (

Int(16 * 64 / 8) == 128) bytes in our exapmle, - But consider a graph of websites and links between them -- that graph would have millions of nodes and edges...

- This is only (

- There are a few approaches to reducing this storage cost:

- Only store the upper triangle of the matrix

- Use

Array{Bool,2}instead ofArray{Int64,2}to store adjacency matrix ( each element onlysizeof(Bool) == 1bit!) - Use a SparseMatrix

- Store as a

Vector{Vector{Int}}

# Vector{Vector{Int}}

A2 = [[2], [1, 3, 4], [2, 4], [2, 3]]4-element Vector{Vector{Int64}}:

[2]

[1, 3, 4]

[2, 4]

[2, 3]G1.fadjlist4-element Vector{Vector{Int64}}:

[2]

[1, 3, 4]

[2, 4]

[2, 3]Graph Theory Concepts¶

- Let’s explore some concepts often used in analysis of graphs

Paths¶

- When studying graphs it is often natural to ask about how things travel or flow across the graph

- For example, how information spreads amongst a group of friends, how data travels the internet, how diseases are transmitted from one person to another, and how people navigate a metro subway system

- In each of these cases, the flow of things goes from node to node across edges

- A flow from one any node to another node is called a path

Degree¶

- The degree of a node is the number of edges connected to it

- In our example graph G1, node B has degree 3 (connected to A, C, and D)

- Node A has degree 1 (only connected to B)

- Degree is a fundamental measure of node importance in a network

- High-degree nodes are often called “hubs”

- In social networks, these might be influential people or “connectors”

- We can compute degree directly from the adjacency matrix

- Degree of node is

- Graphs.jl provides the

degreefunction

degree(G1)4-element Vector{Int64}:

1

3

2

2degree(arpa, node_ints["MIT"])UndefVarError: `arpa` not defined in `Main`

Suggestion: check for spelling errors or missing imports.

Stacktrace:

[1] top-level scope

@ ~/Teaching/UCF/CAP-6318/book-myst/week03/jl_notebook_cell_df34fa98e69747e1a8f8a730347b8e2f_Y164sZmlsZQ==.jl:1- The degree distribution of a network tells us a lot about its structure

- Many real-world networks have a few high-degree hubs and many low-degree nodes

- Social networks: celebrities with millions of followers

- Internet: major websites with many incoming links

- Transportation: hub airports like Atlanta or Chicago

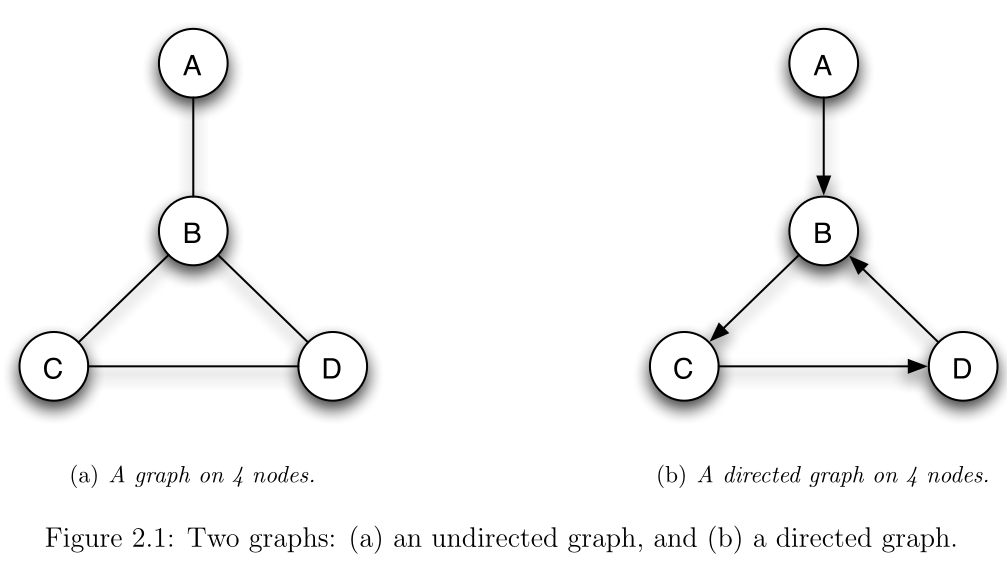

Arpanet Example¶

- Consider the following Graph of the first iteration of the internet

- There are many possible paths through this network

- Consider a path from UCSB to MIT:

UCSB-UCLA-RAND-BBN-MIT - Another possible path from UCSB to MIT is

UCSB-SRI-UTAH-MIT

Graphs.jl Arpanet¶

- Let’s define the Arpanet using Graphs as it will be helpful throughout this lecture

nodes = [

"UCSB" => ["SRI", "UCLA"],

"SRI" => ["UCSB", "UCLA", "STAN", "UTAH"],

"UCLA" => ["SRI", "UCSB", "STAN", "RAND"],

"STAN" => ["SRI", "UCLA"],

"UTAH" => ["SRI", "SDC", "MIT"],

"SDC" => ["UTAH", "RAND"],

"RAND" => ["UCLA", "SDC", "BBN"],

"MIT" => ["UTAH", "BBN", "LINC"],

"BBN" => ["MIT", "RAND", "HARV"],

"LINC" => ["MIT", "CASE"],

"CASE" => ["LINC", "CARN"],

"CARN" => ["CASE", "HARV"],

"HARV" => ["CARN", "BBN"]

]

node_ints = Dict(zip(first.(nodes), 1:length(nodes)))

arpa = SimpleGraph(length(nodes))

for (node, edges) in nodes

for e in edges

add_edge!(arpa, node_ints[node], node_ints[e])

end

end

# save graph for loading in future

savegraph("arpanet.lg", arpa)1arpa{13, 17} undirected simple Int64 graphgplot(arpa, nodelabel=first.(nodes))Loading...

Cycles¶

- An important concept when analyzing graphs is the concept of a cycle

- A cycle is a path that starts and ends at the same node

- For the ARPA net, an example cycle is

LINC-CASE-CARN-HARV-BBN-MIT-LINC - Question... what is the shortest possible cycle in a graph (including all endpoints)?

- Cycles appear frequently in real-world networks

- Friendship networks: if A is friends with B, and B with C, often A and C become friends

- Transportation networks: cyclical routes allow for redundancy and flexibility

- Supply chains: cyclical dependencies can create both resilience and vulnerabilities

Trees¶

- A tree is a connected graph with no cycles

- Trees have exactly N-1 edges for N nodes (the minimum to stay connected)

- Adding any edge to a tree creates a cycle

- Removing any edge from a tree disconnects it

- Trees appear frequently in hierarchical structures

- Organizational charts: CEO at root, departments as branches

- Family trees: ancestors and descendants

- Decision trees: choices branching from initial state

- File systems: directories and subdirectories

- The breadth-first search we’ll see later naturally creates a tree from any graph

# Example: create a simple tree

tree = SimpleGraph(5)

add_edge!(tree, 1, 2)

add_edge!(tree, 1, 3)

add_edge!(tree, 2, 4)

add_edge!(tree, 2, 5)

gplot(tree, nodelabel=1:5)Loading...

is_tree(tree) # Graphs.jl can check if a graph is a treetrueis_tree(G1) # Our original graph has a cycle, so it's not a treefalseConnectedness¶

- A graph is connected if there exists a path between every pair of nodes

- In other words, you can travel from any node to any other node by following edges

- The ARPA network was designed to be connected -- ensuring communication between all sites

- We can check if a graph is connected using Graphs.jl

is_connected(arpa)true- It is natural to believe that many real-world networks are connected

- Transportation: you can get to any station

- Internet: you can visit any website

- But it is entirely possible to have a non-connected graph

- Social networks (nodes: people, edges: friendships) of college students who different countries

- Suppliers for a textile company vs a microchip manufacturer

Distance¶

- We can extend concept of paths between nodes, to include a notion of distance

- The length of a path is the number of steps it takes from beginning to end

MIT-BBN-RAND-UCLAhas length 3 (starting fromMITtake three steps before ending atUCLA)

- The distance between two nodes, is the length of the shortest path between those nodes

- Graphs can compute distances using the

gdistancesfunction - Below we compute the distance between

UCLAand all nodes

Dict(zip(first.(nodes), gdistances(arpa, node_ints["UCLA"])))Dict{String, Int64} with 13 entries:

"HARV" => 3

"UTAH" => 2

"UCSB" => 1

"LINC" => 4

"RAND" => 1

"MIT" => 3

"CASE" => 5

"SRI" => 1

"STAN" => 1

"UCLA" => 0

"SDC" => 2

"CARN" => 4

"BBN" => 2Breadth-First Search¶

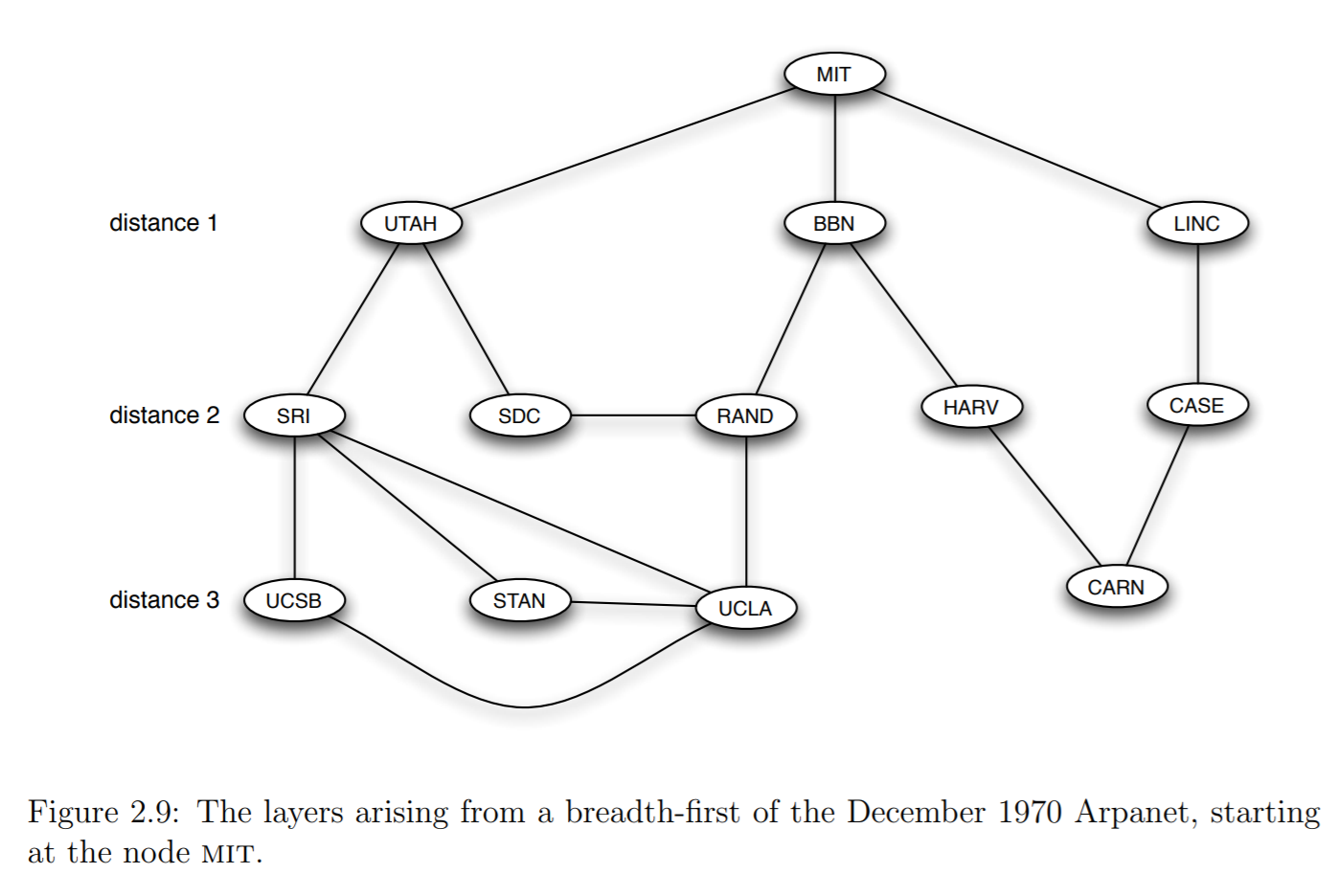

- If asked, how would you go about computing the distance between the

HARVnode and all other nodes? - One iterative approach might be:

- Start with

HARV: note it is distance zero toHARV - Move on to all nodes directly connected to

HARV: these are distance 1 - Then move to all nodes connected to nodes that are distance 1 from

HARV(excluding any you may have already found): declare these to be at distance 2 fromHARV - Continue traversing edges until you have visited all nodes

- Start with

- This algorihtm is called breadth-first search

Example: Breadth-First Search from MIT¶

- The image below shows how breadth-first search would proceed for the MIT node

Exercise (difficult!): BFS¶

- Now it is time for you to try this out!

- Our goal is to use breadth-first search to compute the distance betwen a given node and all other nodes

- The return value you end up with should be an

Vector{Vector{Int}}, where elementiof this vector contains all node labels at distanceifrom the starting node - Fill in the logic for the

breadth_first_distancesfunction below

function breadth_first_distances(g, start::Int)

out = Vector{Int}[]

# use push!(out, new_nodes) to add to out

distance = 0

# TODO: your code here...

# return out

out

endbreadth_first_distances (generic function with 1 method)# Test code

function test_bfd_methods(val, want)

if length(val) == 0

error("Make sure to `push!` on to `out` in your function")

elseif length(val) != maximum(gdistances(arpa, node_ints["HARV"]))

error("`out` has incorrect number of elements")

elseif length.(val) != length.(want)

error("Right number of elements, but not right number in each subvector")

elseif all(map(x12 -> all(sort(x12[1]) .== sort(x12[2])), zip(val, want)))

println("correct!")

end

end

function run_tests()

val = breadth_first_distances(arpa, node_ints["HARV"])

want = [[9, 12], [7, 8, 11], [3, 6, 5, 10], [1, 2, 4]]

test_bfd_methods(val, want)

endrun_tests (generic function with 1 method)# uncomment the code below and run when you are ready to test your code

# run_tests()BFS with Graphs¶

- The Graphs library contains routines implementing breadth-first search

- The main function is called

bfs_tree

bfs_carn = bfs_tree(arpa, node_ints["CARN"]){13, 12} directed simple Int64 graph- Notice that the printout says we have a graph with 13 nodes, 12 edges and it is a directed graph

- Thus far, all graphs we have considered have been undirected

- We have only been concerned about if a connection (edge) exists between nodes

- A directed graph extends the notion of connecting nodes with a direction

- We can now say that things flow across edges from one node to another -- always in the same direction

- Why would the breadth-first search routine return a directed graph instead of the undirected type we started with?

- Let’s visualize it and see if we can understand why

gplot(bfs_carn, nodelabel=first.(nodes))Loading...

- Notice that arrows only flow out of

CARN - They also always flow away from

CARN - The use of directed edges allows Graphs to represent the shortest path from CARN to any other node

- For example

STAN:CARN -> HARV -> BBN -> RAND -> UCLA -> STAN

- For example

Exercise: Explore DiGraph¶

- The

bfs_carnobject has type $(Markdown.Code(string(typeof(bfs_carn)))) - Let’s view the names of its properties (properties)

propertynames(bfs_carn)(:ne, :fadjlist, :badjlist)bfs_carn.fadjlist13-element Vector{Vector{Int64}}:

[]

[]

[1, 2, 4]

[]

[]

[]

[3, 6]

[5]

[7, 8]

[]

[10]

[11, 13]

[9]- The

fadjlist(forward adjacency list) property is aVector{Vector{Int64}} fadjlisthas one element per node (call index into outer Vectorifor nodei)- Each element is itself a vector containing node indices for all nodes

jfor which there is an edge flowing fromitoj - Below we have set up a new method (see below) for the

breadth_first_distancesfunction that takes aDiGraphas an argument - Your task is to implement the the method so that it has the same return value as the previous method from above

function breadth_first_distances(g::SimpleDiGraph, start::Int)

out = Vector{Int}[]

# use push!(out, new_nodes) to add to out

distance = 0

# TODO: your code here...

# return out

out

endbreadth_first_distances (generic function with 2 methods)# test code

function test_digraph_ex()

val = breadth_first_distances(

bfs_tree(arpa, node_ints["HARV"]),

node_ints["HARV"]

)

want = [[9, 12], [7, 8, 11], [3, 6, 5, 10], [1, 2, 4]]

test_bfd_methods(val, want)

endtest_digraph_ex (generic function with 1 method)# uncomment the code below when you are ready to test your code!

# test_digraph_ex()Components¶

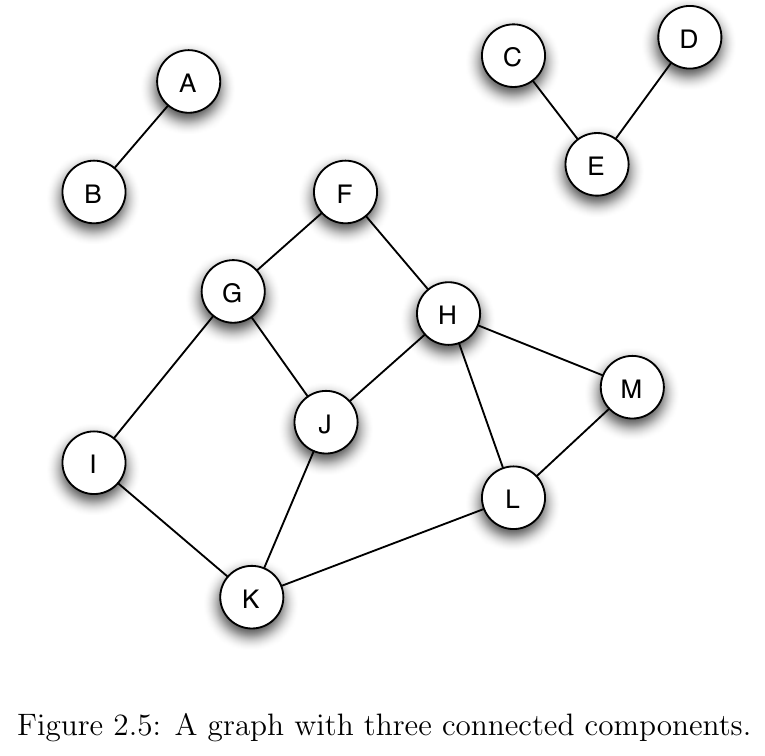

- A component of a graph is a self-contained subset of the nodes

- More precisely, a set of nodes is a component if

- Every node in the subset has a path to every other node in the subset

- The subset is not part of a larger set with property (1)

- Example:

Finding Components¶

- Graphs.jl provides functions to identify and work with components

connected_components(g)returns a vector of vectors, where each inner vector contains the nodes in one component- Let’s create a graph with multiple components and explore it

# Create a graph with three components

multi_component = SimpleGraph(10)

# Component 1: nodes 1, 2, 3

add_edge!(multi_component, 1, 2)

add_edge!(multi_component, 2, 3)

add_edge!(multi_component, 3, 1)

# Component 2: nodes 4, 5, 6, 7

add_edge!(multi_component, 4, 5)

add_edge!(multi_component, 5, 6)

add_edge!(multi_component, 6, 7)

add_edge!(multi_component, 7, 4)

# Component 3: nodes 8, 9

add_edge!(multi_component, 8, 9)

# Node 10 is isolated (its own component)truecomponents = connected_components(multi_component)4-element Vector{Vector{Int64}}:

[1, 2, 3]

[4, 5, 6, 7]

[8, 9]

[10]println("Number of components: ", length(components))

for (i, comp) in enumerate(components)

println("Component $i has $(length(comp)) nodes: $comp")

endNumber of components: 4

Component 1 has 3 nodes: [1, 2, 3]

Component 2 has 4 nodes: [4, 5, 6, 7]

Component 3 has 2 nodes: [8, 9]

Component 4 has 1 nodes: [10]

gplot(multi_component, nodelabel=1:10)Loading...

Why Components Matter¶

- Components help us understand the structure of social networks

- Each component represents a group that can communicate internally but not with other groups

- In social network analysis, components reveal:

- Information silos: Ideas spread within components but not between them

- Echo chambers: Opinions reinforce within isolated groups

- Community detection: Natural groupings in social structures

- Influence boundaries: Limits of where influence can spread

Real-World Implications¶

- Disease spread: Each component represents a boundary for transmission

- COVID-19 travel restrictions aimed to keep countries as separate components

- Contact tracing identifies components to contain outbreaks

- Marketing: Products spread through word-of-mouth within components

- Need to seed each component separately for full market penetration

- Viral marketing campaigns can fail if they don’t bridge components

- Political polarization: Separate components in social media

- Different groups may never see opposing viewpoints

- Bridging nodes between components become crucial for dialogue

- Infrastructure resilience: Power grids, internet backbone

- Multiple components mean system fragmentation after failures

- Redundant connections prevent network from splitting into components

Giant Component¶

- Many real-world networks have a giant component containing most nodes

- Plus several small components or isolated nodes

- Let’s check if ARPANET has this structure

arpa_components = connected_components(arpa)

println("ARPANET has $(length(arpa_components)) component(s)")

println("Component sizes: ", length.(arpa_components))ARPANET has 1 component(s)

Component sizes: [13]

- ARPANET is fully connected (one component) by design

- This ensures any site can communicate with any other site

- Network resilience was a key design goal for the early internet

Real-World Network Examples¶

- Let’s analyze some actual network datasets to see these concepts in practice

- We’ll look at:

- Zachary’s Karate Club: A classic social network dataset

- Facebook ego networks: Social connections from real Facebook data

- Email networks: Communication patterns in organizations

Zachary’s Karate Club¶

- Famous dataset from sociology (Zachary, 1977)

- Documents friendships in a karate club that split into two factions

- 34 members (nodes), 78 friendships (edges)

- Perfect for studying community structure and components

# Graphs.jl includes several famous networks as built-in datasets!

karate = smallgraph(:karate){34, 78} undirected simple Int64 graph# Analyze the karate club network

using Statistics # for `mean` function

println("Karate Club Network:")

println(" Nodes: ", nv(karate))

println(" Edges: ", ne(karate))

println(" Average degree: ", round(mean(degree(karate)), digits=2))

println(" Is connected: ", is_connected(karate))Karate Club Network:

Nodes: 34

Edges: 78

Average degree: 4.59

Is connected: true

# Look at degree distribution

degrees = degree(karate)

println("\nDegree distribution:")

println(" Min degree: ", minimum(degrees))

println(" Max degree: ", maximum(degrees))

println(" Node with most connections: ", argmax(degrees))

Degree distribution:

Min degree: 1

Max degree: 17

Node with most connections: 34

# Visualize the karate club network

gplot(karate, nodelabel=1:nv(karate), nodesize=0.1)Loading...

Exercise: Analyzing the Petersen Graph¶

- The Petersen graph is a famous graph in graph theory

- It appears in many theoretical results and counterexamples

- Your task: analyze this network’s structure

# Load the Petersen graph

petersen = smallgraph(:petersen)

# TODO: Calculate the following properties

num_nodes = missing # Total number of nodes

num_edges = missing # Total number of edges

avg_degree = missing # Average degree (should be the same for all nodes!)

is_it_connected = missing # Is the graph connected?

is_it_tree = missing # Is it a tree?

num_components = missing # How many components?

# Print your results

println("Petersen Graph Analysis:")

println(" Number of nodes: ", num_nodes)

println(" Number of edges: ", num_edges)

println(" Average degree: ", avg_degree)

println(" Is connected: ", is_it_connected)

println(" Is it a tree: ", is_it_tree)

println(" Number of components: ", num_components)Petersen Graph Analysis:

Number of nodes: missing

Number of edges: missing

Average degree: missing

Is connected: missing

Is it a tree: missing

Number of components: missing

Other Built-in Networks¶

- Graphs.jl includes many classic networks for teaching and research

- Some interesting examples you can explore:

# Examples of other built-in graphs

graphs_to_explore = [

:house, # The "house" graph (5 nodes)

:bull, # The bull graph

:cubical, # 3-dimensional cube

:diamond, # Diamond graph

:dodecahedral, # Dodecahedron graph (20 nodes)

:heawood, # Heawood graph (14 nodes)

:moebiuskantor,# Möbius-Kantor graph

:octahedral, # Octahedron graph

:pappus, # Pappus graph

:tutte, # Tutte graph (46 nodes)

]

# Try loading and analyzing one!

# Example: g = smallgraph(:house)10-element Vector{Symbol}:

:house

:bull

:cubical

:diamond

:dodecahedral

:heawood

:moebiuskantor

:octahedral

:pappus

:tutte