Computational Analysis of Social Complexity

Prerequisites

- Julia Basics (from week 2)

- Julia Types (from week 2)

- ABM intro

Outcomes

- Learn to use the Julia REPL for running interactive ABM visualizations

- Implement the Schelling segregation model using Agents.jl

References

Review Schelling Model¶

- Recall the components of the Schelling segregation model

- Environment: 25x25 grid of single family dwellings

- Agents with properties:

- location (x,y) coordinate for current home

- type: orange or blue. Fixed over time. 250 of each

- happiness: 0 if less than of neighbors are of same type, 1 otherwise

- Rules:

- Agents choose to move to unoccupied grid point if unhappy

Note neighbors for a particular cell are the the 8 other cells surrounding the cell of interest. Corner or edge cells have less than 8 neighbors

Agents.jl¶

- We are now ready to get started implementing the Schelling segregation model in Julia

- We’ll use the Agents.jl library, which is a very powerful ABM toolkit

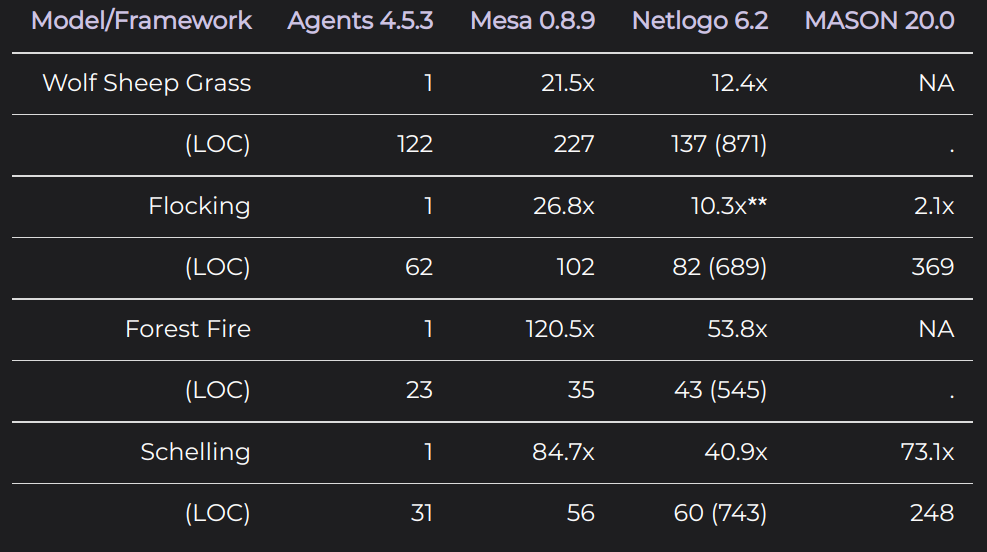

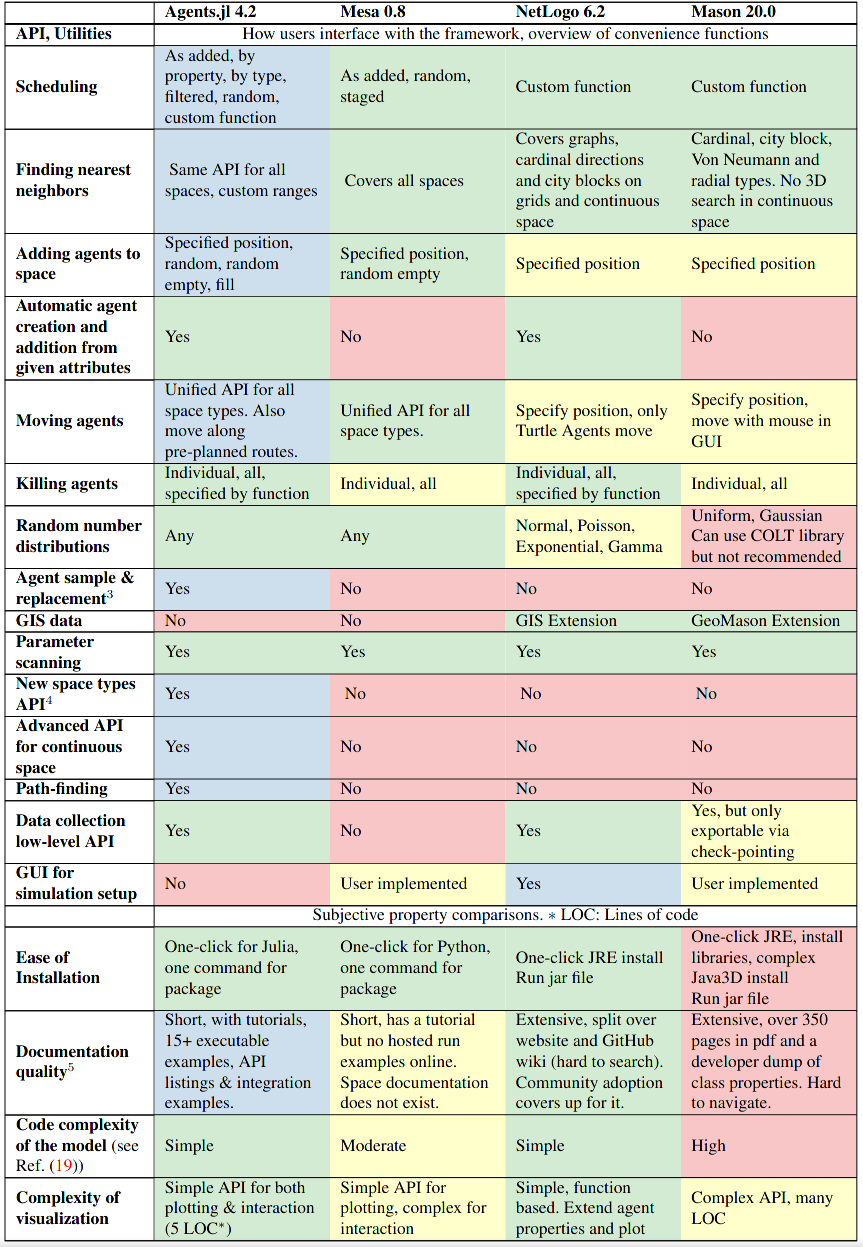

- Here are some points of comparison between Agents.jl and other ABM software (from the Agents.jl website):

Schelling in Agents.jl¶

- Let’s now implement the Schelling Segregation model in Agents.jl

- The first thing we’ll need to do is define our Agent

- The recommended way to do this is to create a new Julia struct using the

@agentmacro provided by Agents.jl - The macro will ensure a few things:

- The struct contains

idandposfields to keep track of the agent and its position - The struct is mutable so the position can be updated

- The struct is a subtype of

AbstractAgentso it can be used by other functions in Agents.jl

- The struct contains

# load up packages we need for this example... might take a few minutes

# import Pkg

# Pkg.activate(".")

# Pkg.instantiate()

using Agents@agent struct SchellingAgent(GridAgent{2})

is_happy::Bool # whether the agent is happy in its position. (true = happy)

group::Int # The group of the agent, determines mood as it interacts with neighbors 0: blue, 1: orange

end- We can see the complete structure of the

ShellingAgenttype using thedumpfunction

dump(SchellingAgent)SchellingAgent <: AbstractAgent

id::Int64

pos::Tuple{Int64, Int64}

is_happy::Bool

group::Int64

Schelling Environment¶

- Our Schelling environment will be one the built-in Agents.jl spaces

- We’ll use

GridSpace

environment = GridSpaceSingle((25, 25); periodic = false)GridSpaceSingle with size (25, 25), metric=chebyshev, periodic=falseRules¶

- The last part of our ABM that we need to specify is the rules for how agents respond to the environment and state

- Our rule is that agents will choose to move to an empty grid space if they have less than

wanted_neighborsneighbors of the same group

- Our rule is that agents will choose to move to an empty grid space if they have less than

- Agents.jl requires us to implement these rules in a method

agent_step!(agent::SchellingAgent, model) - We’ll make use of a couple helper functions provided by Agents.jl:

move_agent_single!: move a single agent to an empty place in the environment. This modifies theposfield of the agentnearby_agents: return an array of all neighbors of a particular agent. This queries theposfield of all agents

function agent_step!(agent::SchellingAgent, model)

want = model.wanted_neighbors

have = 0

for n in nearby_agents(agent, model)

if n.group == agent.group

have += 1

end

end

agent.is_happy = have >= want

if !agent.is_happy

move_agent_single!(agent, model)

end

return

endagent_step! (generic function with 1 method)Combining Agents, Environment, and Rules¶

- We now need to create an instance of the

AgentBasedModel(orABMfor short) type - To construct our instance we need to specify our agent type, our environment, our rules (via

agent_step!function), and any additional properties - These additional properties belong to the model, and can be thought of as parameters that should be calibrated

- In our previous exposition we would have attached these to the environment

properties = Dict(:wanted_neighbors => 4)

schelling = AgentBasedModel(SchellingAgent, environment; properties=properties, agent_step! = agent_step!)StandardABM with 0 agents of type SchellingAgent

agents container: Dict

space: GridSpaceSingle with size (25, 25), metric=chebyshev, periodic=false

scheduler: fastest

properties: wanted_neighborsAdd Agents¶

- Now we have fully specified the behavior of our ABM, but we have a problem...

- We don’t have any agents!!

- To add agents, we’ll use the

add_agent_single!(::SchellingAgent, model)function, which is provided by Agents.jl and knows how to place non-overlapping agents in our environment- This will set the

posfield for our agents

- This will set the

- So that we can run many experiments, we’ll actually create a helper function that will create a new model from scratch and add agents to it

function init_schelling(;num_agents_per_group=250)

environment = GridSpaceSingle((25, 25), periodic=false)

properties = Dict(:wanted_neighbors => 4)

model = ABM(SchellingAgent, environment; properties=properties, agent_step! = agent_step!)

id = 0

for group in 1:2, i in 1:num_agents_per_group

agent = SchellingAgent(id+=1, (1, 1), false, group)

add_agent_single!(agent, model)

end

model

end

model = init_schelling()StandardABM with 500 agents of type SchellingAgent

agents container: Dict

space: GridSpaceSingle with size (25, 25), metric=chebyshev, periodic=false

scheduler: fastest

properties: wanted_neighborsRunning the Model¶

- To run our model, we need to step forward in time

- We do this using the

step!function provided by Agents.jl - This function will iterate over all the agents in the model and call

agent_step!for each of them

# advance one step

step!(model)StandardABM with 500 agents of type SchellingAgent

agents container: Dict

space: GridSpaceSingle with size (25, 25), metric=chebyshev, periodic=false

scheduler: fastest

properties: wanted_neighbors# advance three steps

step!(model, 3)StandardABM with 500 agents of type SchellingAgent

agents container: Dict

space: GridSpaceSingle with size (25, 25), metric=chebyshev, periodic=false

scheduler: fastest

properties: wanted_neighbors- We can also use the

runfunction - This function requires a model, agent_step! function, number of steps and array of agent property names to record

- The output is a DataFrame with all the data

model = init_schelling()

adata = [:pos, :is_happy, :group] # short for agent data

data, _ = run!(model, 10; adata)

dataVisualizing the Agents¶

- One of the more instructive (and fun!) parts of agent based modeling is visualizing the data

- To do this visualization we will use the

abmplotfunction

using CairoMakie

agent_color(a) = a.group == 1 ? :blue : :orange

agent_marker(a) = a.group == 1 ? :circle : :rect

figure, _ = abmplot(model; agent_color, agent_marker, agent_size = 10)

figure # returning the figure displays itAnimating the Agents¶

- We can also create a video that animates our agents moving throughout the system

- We do this using the

abmvideofunction as follows

model = init_schelling();

abmvideo(

"schelling.mp4", model;

agent_color, agent_marker, agent_size = 10,

framerate = 4, frames = 20,

title = "Schelling's segregation model"

)Interactive Application¶

- Agents.jl also makes it very easy to create an interactive application for our model!

- We can do this using the

abmexplorationfunction - This expects a single positional argument:

model

- We also have some keyword arguments

params: Dict mapping model parameters to range of values to testagent_color,agent_marker,agent_size: control marker color color, symbol, and size as beforeadata: Array of (agent_property, summary_func) tuples that specify which data to plot in separate chartsalabels: What label to put on the plots foradata

model = init_schelling()

adata = [(:is_happy, sum)]

alabels = ["n_happy"]

parameter_range = Dict(:wanted_neighbors => 0:8)

figure, abmobs = abmexploration(

model;

adata, alabels,

agent_color, agent_marker, agent_size = 10,

params=parameter_range,

)

figureRunning Julia Code in the REPL¶

- In order to use the interactive app we need to run the code from the Julia REPL (not inside VS Code or Jupyter)

- The REPL (Read-Eval-Print-Loop) is the default way to run Julia interactively

- Let’s learn about the REPL before we run our interactive visualization

The Julia REPL¶

- The REPL is typically started either by typing

juliain a terminal or by clicking on the Julia icon in your Applications list - Once started, you will see a prompt

julia>where you can enter Julia code - If you enter code and press

Enter, the REPL will evaluate the code and print the result

REPL Modes¶

The REPL has several modes you can switch between:

- Default mode

julia>: Run Julia code and see output (default) - Shell mode

shell>: Interact with underlying shell/terminal (activate with;) - Help mode

help?>: Get help on Julia functions (activate with?) - Package mode

pkg>: Manage Julia packages (activate with])

- Default mode

To return to default mode from any other mode, press backspace at an empty prompt

Examples of what each mode prompt looks like:

- Default:

julia> - Shell:

shell> - Help:

help?> - Package:

(@v1.9) pkg>

- Default:

Running our Interactive Schelling Model¶

- Now let’s run our interactive model from the REPL:

- Open a terminal and type

juliato start the REPL - Navigate to this notebook’s directory if needed (using

;for shell mode) - Copy and run the code from the cells above to set up the model

- Run the interactive visualization code

- You’ll be able to adjust parameters with sliders and see the model update in real-time!

- Open a terminal and type

Real-World Implications¶

- Schelling’s model was groundbreaking for urban planning and social policy

- Key insight: segregation doesn’t require intense prejudice - even mild preferences for similar neighbors create strong patterns

- Applications beyond racial segregation:

- Income clustering in neighborhoods

- Social media echo chambers and political polarization

- Clustering in high school cafeterias

- Academic discipline segregation in universities

- Model limitations: Reality includes housing costs, school quality, employment access, historical policies

- Policy implication: Simply reducing prejudice may not eliminate segregation - structural interventions may be needed

Exercises¶

Exercise 1: Parameter Sensitivity Analysis¶

Using the interactive app or by modifying the code, explore how different wanted_neighbors values affect segregation:

- Run the model with

wanted_neighbors = 1(agents want just 1 similar neighbor)- Observe the final pattern. Is there segregation?

- Run with

wanted_neighbors = 3(moderate preference)- How does the pattern differ? How many steps to stability?

- Run with

wanted_neighbors = 6(strong preference)- What happens? Do all agents become happy?

- Document your findings:

- At what threshold does segregation become noticeable?

- What happens when the threshold is too high?

- How does empty space (less than 500 agents total) affect the patterns?

Exercise 2: Model Extensions¶

Modify the Schelling model to explore these variations:

Three groups instead of two:

- Add a third group (e.g., green agents)

- What patterns emerge with three groups?

- Hint: Modify the

init_schellingfunction to havefor group in 1:3

Asymmetric populations:

- Try 400 agents of group 1 and 100 agents of group 2

- Does the minority group cluster more tightly?

- What happens to the majority group’s distribution?

Different happiness thresholds per group:

- Modify so group 1 wants 3 similar neighbors, group 2 wants 5

- Which group ends up more segregated?

- What does this suggest about tolerance and outcomes?

Distance-based happiness (Advanced):

- Instead of just counting similar neighbors, weight them by distance

- Immediate neighbors count as 1.0, diagonal neighbors as 0.7

- How does this change the segregation patterns?

Choose at least one modification to implement and document your observations.