Computational Analysis of Social Complexity

Fall 2025, Spencer Lyon

Prerequisites

- Intro to Game Theory

Outcomes

- Know how to solve for a Nash Equilibrium in mixed strategies

- Understand the concepts of a repeated game and be able to reason about equilibria in such games

- Understand how normal form and extensive form games are related

References

- Easley and Kleinberg chapter 6

Properties¶

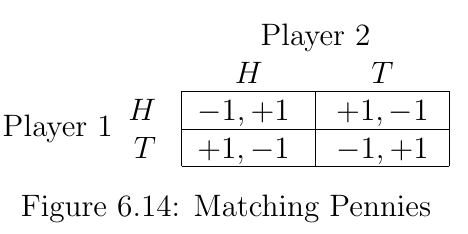

- Matching pennies is an example of a wider class of games

- Some of its properties are that it is

- Zero-sum: sum of payoffs from all players is always 0. One player loses, the other wins

- No Nash Equilibrium in Pure Strategies

- b/c no NE in PS, beneficial to introduce randomness into actions

- Zero sum games are very common

- Example: D-Day in WW2. US could have landed in France on Normandy or Calais. Germany could have put bulk of defenses at one of these places. Outcome largely depended on US ability to trick Germany into putting defenses at Calais

Mixed Strategies¶

- A pure strategy is a selection of a single action from set of possible strategies

- A mixed strategy is a probability distribution over the set of possible strategies

- Pure strategy is a special case of a mixed strategy -- a degenerate distribution

Expected Payoffs¶

- When dealing with pure strategies we could determine payoffs by reading off an appropriate value from the payoff matrix

- With mixed strategies we have to deal with expected payoffs

P1 Payoffs in Matching Pennies¶

- Suppose you are player 1 in matching pennies

- Suppose further that P2 is following a strategy to play H with probability and T with probability

- The expected payoffs from each of P1’s pure strategies are:

- Plays H: :

- Plays T: :

Indifference¶

- Argument: it cannot be optimal for P2 to follow the (q, 1-q) strategy unless it makes P1 indifferent about playing H or T

- Why? Suppose . Then P1 will always pick H, which would in turn make P2 want to change behavior to always play

- Similar logic applies if

- So, it must be that

- This means

Comment¶

- Notice that we used P1’s expected payoffs to determine the mixed strategy for P2

- There are two major themes here

- To derive optimal behavior for one player, you must consider impact of that player’s decisions on the rewards to other players

- P2’s ability to commit to following the (q, 1-q) both allowed P1 to reason about payoffs AND made P1 indifferent about his/her own choice. Commitment is a major theme in advanced game theory, and one we’ll revisit later in the course when we talk about blockchains and smart contracts

P1’s action¶

- We now know (based on P1s expected payoffs) that P2 will do 50/50 split between H and T

- Now consider game from P2’s perspective, taking as given that P1 will be playing H with probability and T with probability

- Exercise: use P2’s expected payoffs under the (p, 1-p) strategy for P1 to determine the value of . What is that value? does it surprise you? Why or Why not?

Asymmetry: NFL play choice¶

- Matching pennies is a particularly simple example of a zero-sum game with no equilibira in pure strategies

- The symmetry in the payoff matrix led to a “boring” outcome

- Let’s consider another example that doesn’t have this symmetry

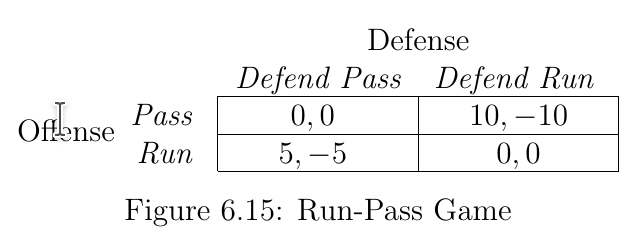

- Consider an American football game

- Each play

- the offense can choose to call a run or pass play

- The defense can choose to focus play call on defending run or defending pass

- The payoff for offensive team is how many yards they gain

- Payoff for defense is always negative and equal to “-” yards gained by offense

- Payoffs based on play calls are given below

Exercise¶

- Given what we’ve learned about mixed strategies, determine the equilibrium probability that the defense chooses to defend the pass (call this ) and the equilibrium probability that the offense chooses a pass play (call this )

Comments¶

- In the run/pass example we see that the higher payoff option for the offense is to pass, but that they choose it less than the lower payoff run option

- Why?

- The main idea is that the threat of a successful pass play causes the defense to choose to defend the pass more than 50% of the time.

- The offense takes that strategy as given, and realizes they are better off running more than 1/2 the time

- Any deviation by the offense to pass more often than the you computed would cause the defense to always defend the pass

- This would result in a strictly worse expected payoff for the offense

Dynamic Games¶

- So far the games we’ve studied have all been static

- By this we mean each participant makes exactly one choice at exactly the same time

- Game theory is far more rich than this!

- We now introduce the concept of a dynamic game

- Our treatement will focus on non-simultaneous decisions

- Study of repeated games is beyond our scope for now

Example: Firm Advertising¶

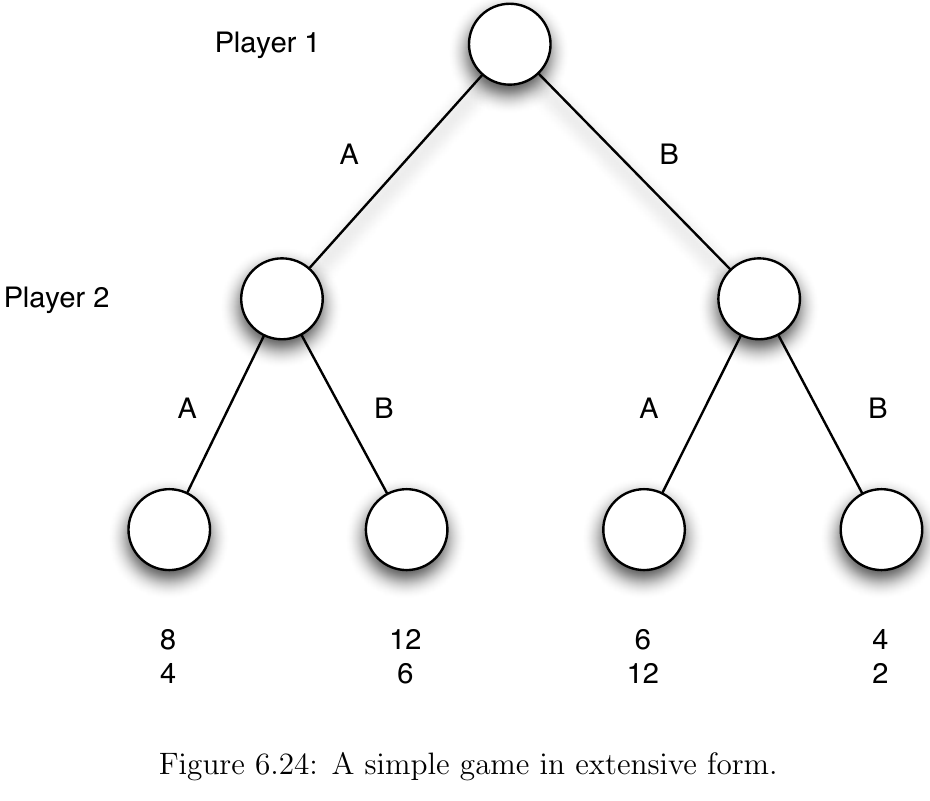

- Consider a game with two firms (1 and 2) and two new markets (A and B)

- Market A has a total of 12 profit to be gained and market B has total of 6 profit

- Both firms have to choose which market to advertise to

- Firm 1 gets to choose first

- Because of the earlier choice, firm 1 has “first mover advantage”

- If firms choose same market, firm 1 gets 2/3 of potential profit and firm 2 gets 1/3

- If they advertise to separate markets, each firm gets all potential profit in their chosen market

Extensive form¶

- We can represent the game we just described as a tree (or directed graph, if you prefer)

- Each node represents a decision point and each branch represents a particular action being chosen

- The game tree for the advertising game is given below

Equilibrium via Game Tree¶

- We can use the extensive form representation of a dynamic game to determine the equilibrium outcome

- The approach for doing this is to start at the bottom of the tree and work our way up

- In this example we first start with Player 2 and determine what decision should be made at each decision node:

- If on branch from P1 choosing A, P2 should choose B because (6 > 4)

- If on branch from P1 choosing B, P2 should choose A because (12 > 2)

- Now that we know what P2 will do at each node, we go up the tree to P1s decision

- P1 knows P2 will choose the opposite of P1’s choice

- So P1 realizes that (12 > 6), so P1 chooses

- The equilibrium of this game is (A, B)

Example: Market Entry¶

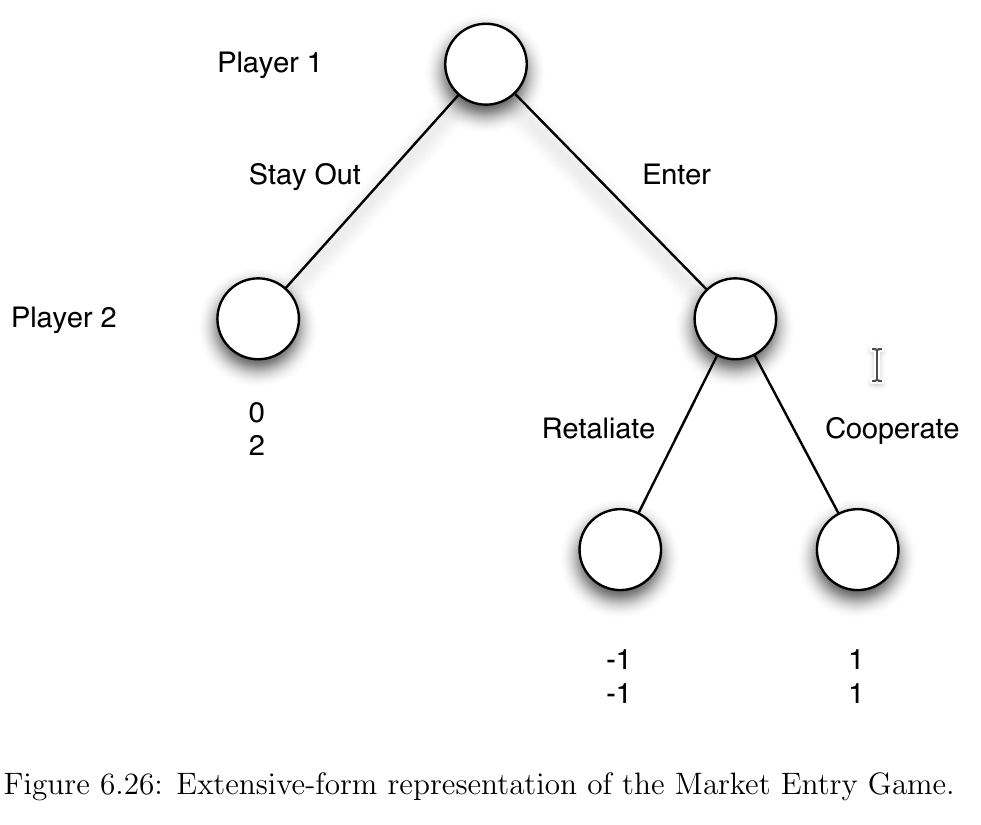

- Let’s consider a similar game

- Player 2 is now an incumbent (already existing firm) and player 1 is a startup deciding to enter the market or stay out

- If P1 chooses to stay out (S), the game ends and P2 is happy

- If P1 chooses to enter (E), P2 can choose to retaliate or cooperate

- Payoffs are given in game tree below

Exercise¶

- Apply the logic outlined above when studying the advertising game to determine the equilibrium outcome of the Market Entry Game

- What does Player 1 choose to do?

- Does player 2 have to make a choice? If so, what is it?

Comparison to Normal Form¶

- Consider the market entry game in normal form

- Notice that in this normal form game there are two NE in pure strategies:

- (S, R): An equilibrium that didn’t come up in the dynamic game, because P1 got to move first and chose to enter

- (E, C): the equilibrim we’ve already seen

- Key idea: taking into account timing may change equilibrium outcomes

- If P2 had the ability to commit to retaliate, then perhaps P1 would choose to stay out

- Again commitment is a key concept in Game theory

- Book talks about “if P2 could commit to having a computer play its strategies”

- This is not just a hypothetical if -- smart contracts make it possible and enforce it!