Computational Analysis of Social Complexity

Fall 2025, Spencer Lyon

Prerequisites

- Networks

- Game Theory

Outcomes

- Represent network traffic weighted DiGraph

- Analyze equilibrium network outcomes using the concept of Nash Equilibirum

- Understand Braes’ paradox

- Learn about the concept of social welfare and a social planners

References

- Easley and Kleinberg chapter 8

Congestion¶

- We regularly use physical networks of all kinds

- Power grids

- The internet

- Streets

- Railroads

- What happens when the networks get congested?

- Typically -- flow across the network slows down

- Today we’ll study how game theoretic ideas are helpful when analyzing how a network with finite capacity or increasing costs

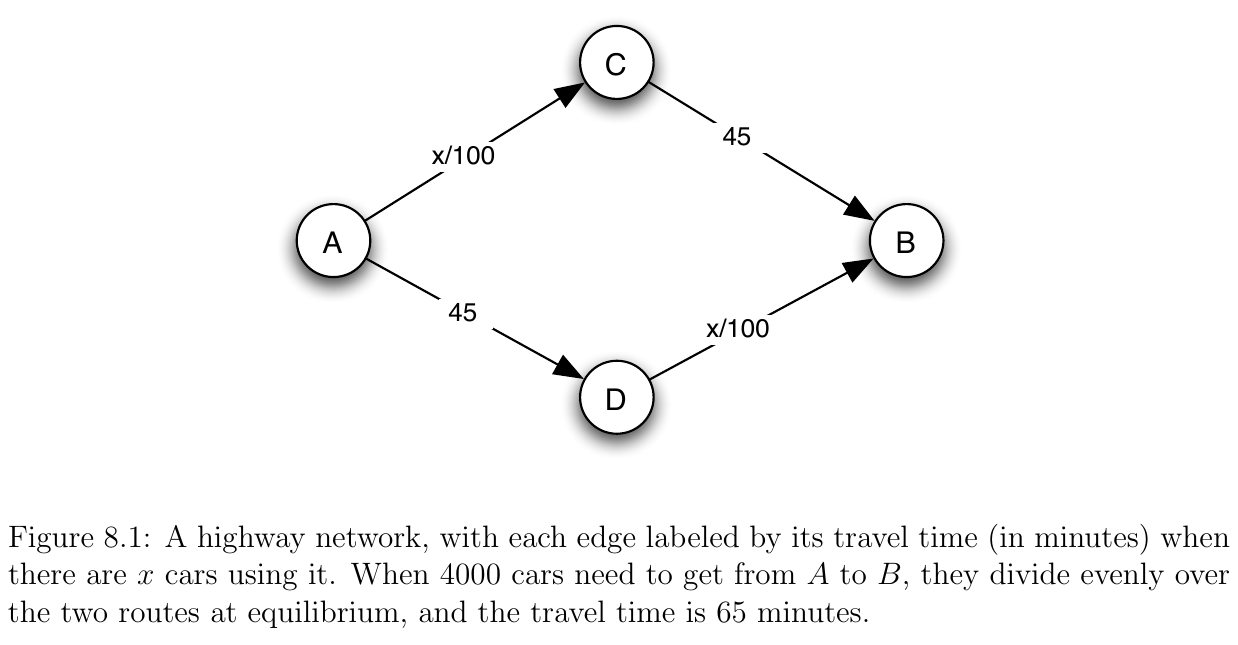

A Traffic Network¶

- We’ll start by considering a traffic network

- The figure caption has extra detail -- so be sure to read it!

- We’ll write up some helper Julia functions that will let us create and visualize the traffic network for arbitrary values of x

using Graphs, SimpleWeightedGraphs, GraphPlotfunction traffic_graph1(x)

A = [

0 0 x/100 45;

0 0 0 0;

0 45 0 0;

0 x/100 0 0

]

SimpleWeightedDiGraph(A)

endtraffic_graph1 (generic function with 1 method)function plot_traffic_graph(g::SimpleWeightedDiGraph)

locs_x = [1.0, 3, 2, 2]

locs_y = [1.0, 1, 0, 2]

labels = collect('A':'Z')[1:nv(g)]

gplot(g, locs_x, locs_y, nodelabel=labels, edgelabel=weight.(edges(g)))

endplot_traffic_graph (generic function with 1 method)plot_traffic_graph(traffic_graph1(10))- Try changing the argument to

traffic_graph1to see how the network changes

The Game¶

- Now suppose, as indicated in the figure caption, that we have 4,000 drivers that need to commute from A to B in the morning

- If all take the upper route (A-C-B) we get a total time of 40 + 45 = 85 minutes

- If all take the lower route (A-D-B) we get a total time of 40 + 45 = 85 minutes

- If, however, they evenly divide we get a total time of 20 + 45 = 65 minutes

Equilibrium¶

- Recall that for a set of strategies (here driving paths) to be a Nash Equilibrium, each player’s strategy must be a best response to the strategy of all other players

- We’ll argue that the only NE of this commuting game is that 2,000 drivers take (A-C-B) and 2,000 take (A-D-B) and everyone takes 65 minutes to commute

Exercise¶

- Show that this strategy (2,000 drivers take (A-C-B) and 2,000 take (A-D-B)) is indeed a Nash equilibrium

- To do this recognize that the game is symmetric for all drivers

- Then, argue that if 3,999 drivers are following that strategy, the best response for the last driver is also to follow the strategy

Numerical Verification¶

Let’s verify why the 50-50 split is indeed an equilibrium:

Current equilibrium: 2,000 drivers on each path, everyone takes 65 minutes

If you’re driver #2,001 considering which path to take:

If you join the upper path (A-C-B):

- Edge A-C now has 2,001 drivers: 2,001/100 = 20.01 minutes

- Edge C-B still takes 45 minutes

- Total time: 20.01 + 45 = 65.01 minutes

If you join the lower path (A-D-B):

- Edge A-D now has 2,001 drivers: 2,001/100 = 20.01 minutes

- Edge D-B still takes 45 minutes

- Total time: 20.01 + 45 = 65.01 minutes

Result: Both paths give the same travel time! No driver has an incentive to switch paths. This confirms our Nash equilibrium.

- Your work HERE!

Discussion¶

- Note a powerful outcome here -- without any coordination by a central authority, drivers will automatically balance perfectly in equilibrium

- The only assumptions we made were:

- Drivers want to minimize driving time

- Drivers are allowed to respond to the decisions of others

- The first assumption is very plausable -- nobody wants to sit in more traffic than necessary

- The second highlights a key facet of our modern society...

- Information availability (here decisions of other drivers) can (and does!) lead to optimal outcomes without the need for further regulation or policing

function traffic_graph2(x) G = traffic_graph1(x) # Add an edge with minimal weight (1e-16 instead of 0) because # GraphPlot doesn’t display edges with weight 0 add_edge!(G, 3, 4, 1e-16) G end

function traffic_graph2(x)

G = traffic_graph1(x)

# need to add an edge with minimal weight so it shows up in plot

add_edge!(G, 3, 4, 1e-16)

G

endtraffic_graph2 (generic function with 1 method)plot_traffic_graph(traffic_graph2(10))Exercise¶

- Is a 50/50 split of traffic still a Nash equilibrium in this case?

- Why or why not?

- Is all 4,000 drivers doing (A-C-D-B) a Nash equilibrium?

- Why or why not?

Braess’ Paradox¶

- In the previous exercise, we saw a rather startling result...

- Doing a network “upgrade” -- adding a wormhole connecting C and D -- resulted in a worse equilibrium outcome for everyone!

- The equilibrium driving time is now 80 minutes for all drivers instead of 65 minutes (which was the case before the wormhole)

- This is known as Braess’ paradox

Real-World Examples¶

Braess’ paradox is not just theoretical - it has been observed in real traffic networks:

New York City (1990): When 42nd Street was closed for Earth Day, traffic flow actually improved rather than worsened. The city later made some closures permanent.

Stuttgart, Germany (1969): After investing in a new road to ease congestion, traffic conditions worsened. The road was eventually removed, restoring better traffic flow.

Seoul, South Korea (2003): The demolition of the Cheonggyecheon highway led to improved traffic conditions, contrary to predictions of chaos.

These cases demonstrate that sometimes removing network capacity can lead to better equilibrium outcomes - a counterintuitive result that game theory helps us understand!

Follow ups¶

- Braess’ paradox was the starting point for a large body of research on using game theory to analyze network traffic

- Some questions that have been asked are:

- How much larger can equilibrium travel time increase after a network upgrade?

- How can network upgrade be designed to be resilient to Braess’ paradox?

Social Welfare¶

- Many economic models are composed of individual actors who make autonomous decisions and have autonomous payoffs

- We’ve been studying some of these settings using tools from game theory, focusing on the individual perspective

- Our notion of equilibrium is dependent on no individual wanting to change strategy in response to other strategies

- Another form of analysis works at the macro level -- we analyze the total payoff for all agents (i.e. sum of payoffs)

- We call this aggregate payoff social welfare

The Social Planner¶

- In an economic model, someone who seeks to maximize social welfare is called a social planner

- A social planner is given the authority to make decisions for all agents

- In our traffic model, a social planner would choose to ignore the wormhole and have 1/2 the drivers take A-C-B and the other half take A-D-B

- In this case everyone would be better off with a cost of 65 minutes instead of the equilibrium 80 minutes

Cost of Freedom¶

- Question: in a generic traffic model, how much worse can the equilibrium outcome be than the social optimum?

- In our example,

- Optimal social welfare is 4000 * 65 = 260,000 total minutes

- Equilibrium social welfare is 4000 * 80 = 320,000 total minutes

- A change of 60,000 total minutes

- Price of Anarchy: This ratio of equilibrium cost to optimal cost is formally called the Price of Anarchy

- Price of Anarchy = Worst Nash Equilibrium Cost / Social Optimum Cost

- In our example: PoA = 320,000 / 260,000 = 1.23 (the equilibrium is 23% worse than optimal)

- To answer this question for a general traffic model, we need to be able to compute the equilibrium for a generic traffic model

- We may study this next week, or perhaps even on your homework 😉