Computational Analysis of Social Complexity

Fall 2025, Spencer Lyon

Prerequisites

- Introduction to Graphs

- Strong and Weak Ties

Outcomes

- Understand the concept of homophily

- Practice working through “by hand” examples of diagnosing homophily

- Be prepared to computationally diagnose homophily in a large network

References

- Easley and Kleinberg chapter 4 (especially section 4.1)

Datasets

- Florentine family relationships: https://

www .cs171 .org /2018 /assets /instructions /lab8 /Lab8 .html

Introduction¶

Main Idea¶

- Consider your friends. Do they tend to

- Enjoy the same movies, music, hobbies as you?

- Hold similar religious or political beliefs?

- Come from similar schools, workplaces, or socio-economic settings?

- What about a random sample of people in the world?

- If you are like me, your answers likely indicate that you have more in common with your friends than you would expect to have with a random sample of people

- This concept -- that we are similar to our friends -- is called homophily

Homophily in Graphs¶

- In the context of graphs or networks, homophily means that nodes that are connected are more similar than nodes at a further distance in the graph

- But what do we mean by more similar?

- Idea: We might have common friends.

- This is an intrinsic force that led to node formation (e.g. triadic closure)

- Alternative: We may share characteristics or properties that are not represented in the graph -- external forces.

- Examples: same race, gender, school, employer, sports team, etc.

- Idea: We might have common friends.

- These external forces are what homophily captures

Context¶

- To identify if homophily is active in a network, we must have access to context on top of list of nodes and edges

- One way to represent this context would be with a DataFrame in addition to a graph:

- One row per node

- One column indicating the node identifier (or just use row number)

- One column for additional characteristic

using DataFrames, Graphs, GraphPlot

df1 = DataFrame(

family=[

"Acciaiuoli", "Albizzi", "Barbadori", "Bischeri", "Castellani",

"Ginori", "Guadagni", "Lamberteschi", "Medici", "Pazzi",

"Peruzzi", "Ridolfi", "Salviati", "Strozzi", "Tornabuoni"

],

wealth=[10, 36, 55, 44, 20, 32, 8, 42, 103, 48, 49, 27, 10, 146, 48],

priorates=[53, 65, missing, 12, 22, missing, 21, 0, 53, missing, 42, 38, 35, 74, missing],

)Loading...

- It will be easier to do our homohpily calculations with binary data,

- we’ll create new columns,

high_wealthandhigh_powerif the wealth and priorates columns, respectively, are above the column medians

using Statistics

df1[!, :high_wealth] = df1.wealth .> median(df1.wealth)

df1[!, :high_power] = df1.priorates .> median(df1.priorates[.!(ismissing.(df1.priorates))])

df1[ismissing.(df1.priorates), :high_power] .= false

df1

Loading...

marriages = [

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0

0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0

0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0

0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 0

0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 0

0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 1

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0

0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 1

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0

0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0

0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0

]

g1 = Graph(marriages){15, 20} undirected simple Int64 graphgplot(g1, nodelabel=df1.family)Loading...

Measuring Homophily¶

- Our discussion on homophily so far has been conceptual... let’s make it precise

- We’ll frame the discussion in terms of a null hypothesis

- Concept should be familiar from statistics, but not exactly the same we we won’t make distributional assumptions

Random Homophily¶

- Our analytical approach begins with a thought experiment (counter factual) that all edges are randomly formed

- In this case, we should not expect the context around our graph to help us predict its structure

- Suppose we consider a characteristic

- We have nodes and of them exhibit feature and of them to not

- We’ll work with probabilities:

- The probability that an arbitrary edge is between two nodes that both share is equal to

- Probability of edge between two non nodes:

- Probabillity of edge bewtween one and one non :

- This will be our “random edge formation” benchmark

Counting Frequencies¶

- Now an empirical value...

- Let there be edges

- Let...

| variable | meaning |

|---|---|

| # edges between 2 | |

| # edges between 2 not | |

| # edges between 1 and 1 not |

- Then

- We’ll use these 4 numbers to count frequencies of edges between types and non- types

Testing for Homophily¶

- We are now ready to test for homophily

- We’ll consider the assumption (null hypothesis) that there is no homophily in characteristic

- observed proportion of cross-characteristic edges is (approximately) the same as characteristic frequencies in the full population

- To test this assumption, we compare

- : the likelihood of a cross-characteristic edge forming, under the assumption of purely random edge formation

- : the proportion of cross-characteristic edges that exist in the network

- When comparing these statistics, we could get one of three outcomes:

| Condition | result |

|---|---|

| inverse homophily | |

| no homophily | |

| homophily |

- Intuition: If observed cross characteristic edge formation is significantly less than what we’d expected under random edge formation, we reject the hypothesis that homophily is not present, and conclude that characteristic is meaningful for edge formation

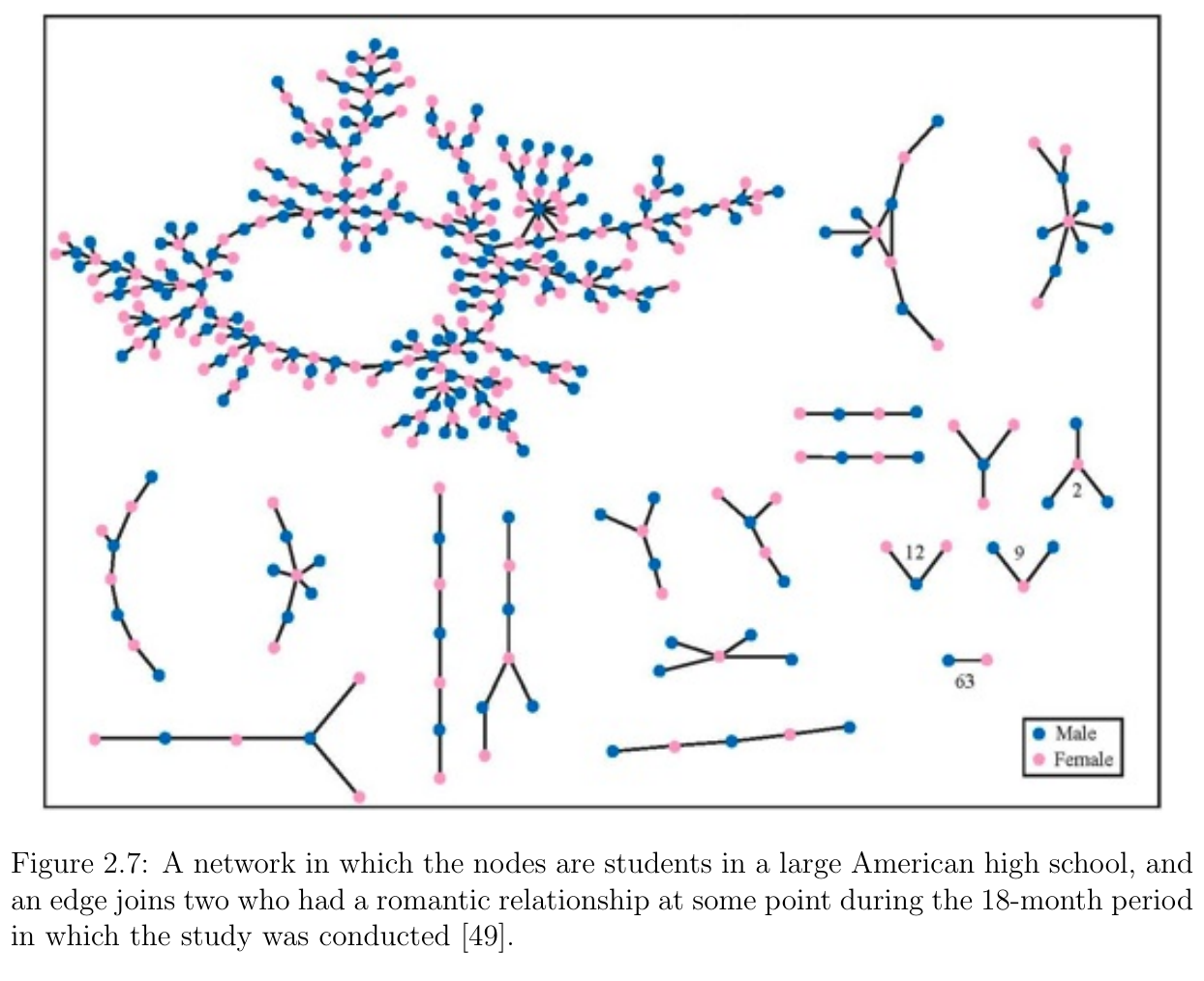

Example: high school relationships¶

- Recall the graph of romantic relationships between high school students

- Question: does this graph exhibit homophily in gender? Why?

Example: Florentines¶

- Let’s work through an example of numerically dianosing homophily using the Florentine data

- I’ll repeat the data below

df1Loading...

node_color = map(x -> x ? "blue" : "red", df1.high_wealth)

gplot(g1, nodelabel=df1.family, nodefillc=node_color)Loading...

Step 1: Counting frequencies¶

- First we need to count frequencies for all our characteristics

- We’ll do that here

using DataStructuresfunction count_frequencies(vals)

counts = DataStructures.counter(vals)

total = length(vals)

Dict(c => v / total for (c, v) in pairs(counts))

endcount_frequencies (generic function with 1 method)count_frequencies(df1.high_wealth)Dict{Bool, Float64} with 2 entries:

0 => 0.6

1 => 0.4Dict(

n => count_frequencies(df1[!, n])

for n in names(df1)[4:end]

)Dict{String, Dict{Bool, Float64}} with 2 entries:

"high_wealth" => Dict(0=>0.533333, 1=>0.466667)

"high_power" => Dict(0=>0.666667, 1=>0.333333)Step 2: Counting Edges¶

- Next we need to count the number of edges of each type

- This step is a bit tricker as it will require that we access both data from the Graph and the DataFrame

- To not spoil the fun, we’ll leave this code as an exercise on the homework

- For now we’ll look at things “by hand”

- Let’s consider

high_wealthand test if marriages where influenced by mutual wealth - Data: We have 7 high wealth families in the dataset

- Counting edge types for high_wealth vs non high_wealth:

- high-high edges: 6

- low-low edges: 3

- Cross edges (high to low): 11

- Total: 11 + 6 + 3 = 20 edges ✓

- The ratio of cross edges is 11/20 = 0.55

- The ratio of nodes that are high is 7/15 = 0.46 ()

gplot(g1, nodelabel=df1.family)Loading...

E = ne(g1)

Exy = 11 # cross edges

n_high = 7

N = nv(g1)

px = n_high / N

# test

2 * px * (1-px), Exy/E(0.49777777777777776, 0.55)- Here we have that the actual proportion of cross edges (0.55) is slightly higher than what we’d expect under random formation (0.5)

- This suggests a very mild instance of inverse homophily (opposites attract), though the difference is quite small

- This does make some sense, as anecdotally we have heard tales of parents desiring their daughters to marry into a wealthy family

Exercise¶

- Repeat the counting exercise, but for the high_power characteristic

- What do you find? Do you see homophily in this characteristic?