Prerequisites

- Introduction to Graphs

- Strong and Weak Ties

- Weighted Graphs

Outcomes

- Understand the structural balance property for sets of three nodes

- Understand the structural balance theorem for a graph

- Recognize structural balance in a weighted graph

References

- Easley and Kleinberg chapter 5 (especially section 5.1-5-3)

Introduction¶

- We now shift our discussion to the notion of whether or not a network is balanced

- For this discussion we will use weighted graphs, where weights are one of

- 1: if nodes are friends (also called

+) - 0: if they don’t know eachother

- -1: if nodes are enemies (also called

-)

- 1: if nodes are friends (also called

- We won’t consider strength of ties right now

- We will also limit discussion to complete graphs (cliques) where all nodes are connected to all other nodes

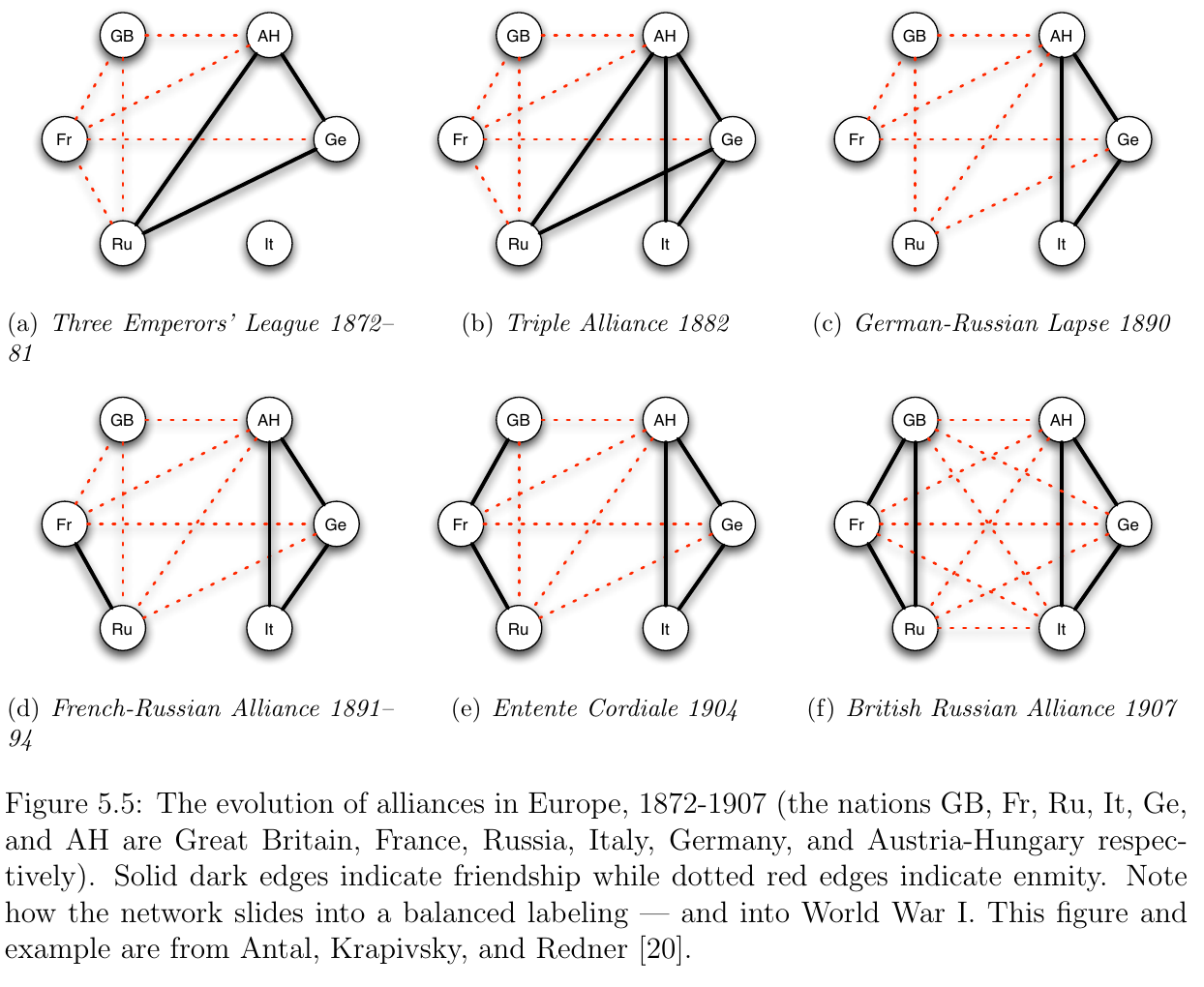

Balance in Triangles¶

- To start thinking about balance, consider the possible configurations of

+and-edges in a triangle - There are 4 options as shown below

- In (a) all people are friends -- this is happy and balanced

- In (c) A-B are friends with a common enemy C -- nobody has reason to change alliances => balanced

- In (b) A is friends with B and C, but they are enemies -- B and C may try to flip A against other => not balanced

- In (d) all are enemies -- two parties have incentive to team up against common enemy => not balanced

Balance In Graphs¶

- This definition of balance in triangles can be extended to graphs

- A complete graph G satisfies the Structural Balance Property if for every set of three nodes, exactly one or three of the edges is labeled

+

Implications: Balance Theorem¶

- One implication of the Structural Balance Property is the Balance Theorem

If a labeled complete graph is balanced, then either all pairs of nodes are friends, or else the nodes can be divided into two groups, X and Y , such that every pair of nodes in X like each other, every pair of nodes in Y like each other, and everyone in X is the enemy of everyone in Y .

- Notice the strength of the statement: either all

+or two mutually exclusive groups of friends that are all enemies with other group

Proving Balance Theorem¶

- We will provide some intuition for how to prove the Balance Theorem, which will help us understand why it is true

- Consider a complete Graph

G - Two alternative cases:

- Everyone is friends: satisfies theorem by definition

- There are some

+and some-edges: need to prove

- For case 2, we must be able to split G into and where the following hold

- Every node in is friends with every other node in

- Every node in is friends with every other node in

- Every node in is enemies with every node in

Proof by construction¶

- Start with complete, balanced graph (our only assumption!)

- We will prove the balance theorem by constructing sets and and verifying that the members of these sets satisfy the 3 properties outlined above

- To start, pick any node

- Divide all other nodes that are friends with into and enemies into

- Because is complete, this is all nodes

Condition 1: ¶

- Let

- We know and

- Because graph is balanced, this triangle must have 1 or 3 +

- There are already 2, so it must be that

- B, C were arbitrary, so this part is proven

Condition 2: ¶

- Let

- We know and

- Because graph is balanced, this triangle must have 1 or 3 +

- There no + and only one option left, so it must be that

- D, E were arbitrary, so this part is proven

Condition 3: and ¶

- Let and

- We know and

- Because graph is balanced, this triangle must have 1 or 3 +

- There is one + () and only one option left, so it must be that

- B, D were arbitrary, so this part is proven

Summary¶

- We’ve just proven that for any complete, balanced graph ; we can partition into sets and that satisfy the group structure of all friends or two groups of friends

- This has interesting implications for fields like social interactions, international relations, and online behavior

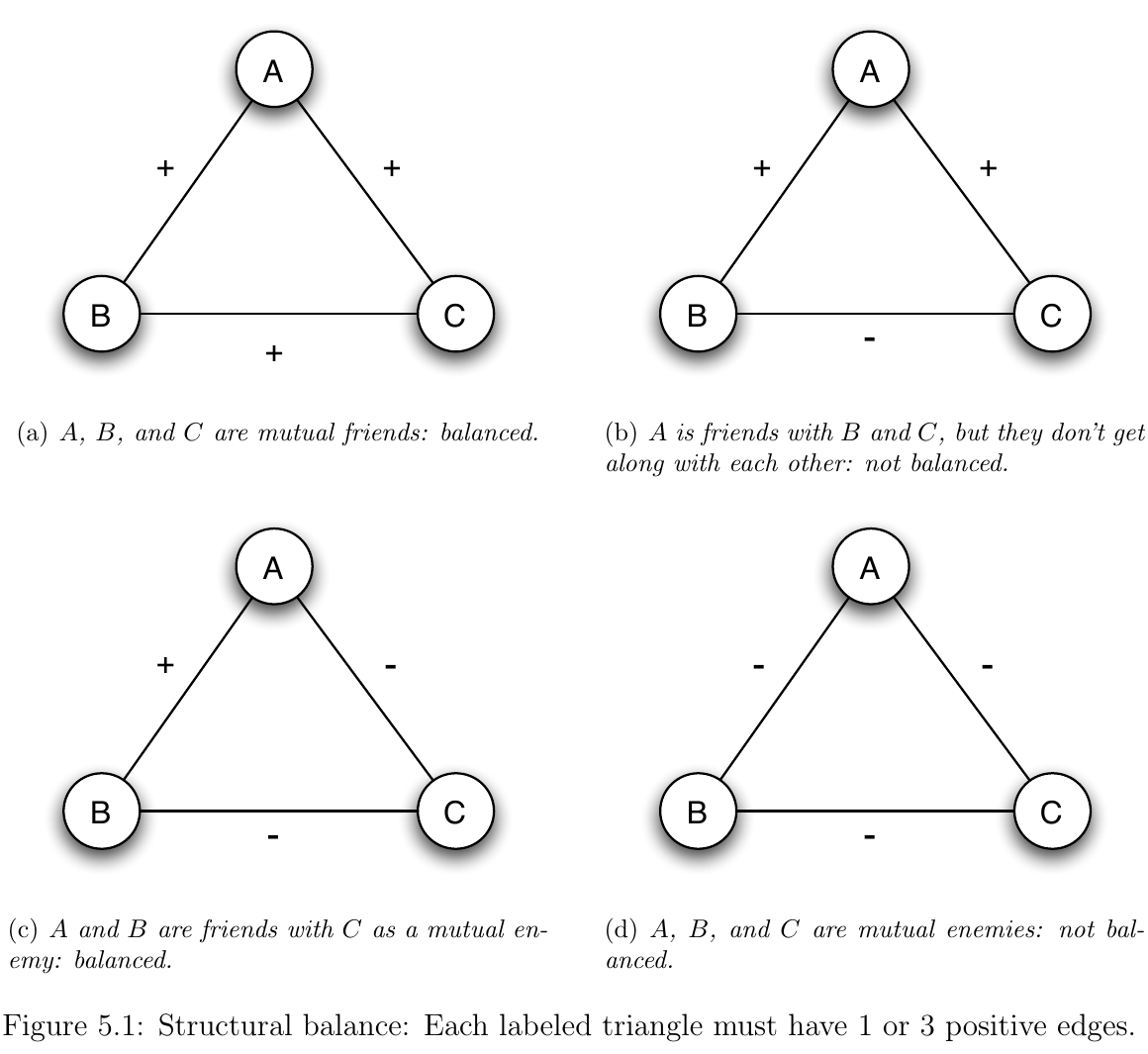

Application: International Relations¶

- Consider the evolution of alliances in Europe between 1872 and 1907 as represented in the graphs below