Prerequisites

- Introduction to Graphs

- Strong and Weak Ties

Outcomes

- Know what a weighted graph is and how to construct them using

SimpleWeightedGraphs.jl - Implement the shortest path algorithm for traversing a weighted graph

References

- Easley and Kleinberg chapter 5 (especially section 5.1-5-3)

# import Pkg; Pkg.add("SimpleWeightedGraphs")using Graphs, GraphPlot, SimpleWeightedGraphsIntroduction¶

- So far we have considered a few types of graphs

- Undirected graph: nodes and are connected by an edge

- Directed graph: connection from node to node

- Strong/weak graphs: each edge is labeled as strong or weak

- Today we extend our understanding of networks to talk about weighted graphs

- Each edge is assigned a

floatdenoting the strength of tie - Ties can be positive (friends) or negative (enemies)

- Can also very in strength (+2.0 better friends than +0.2)

- Each edge is assigned a

Weighted Adjacency Matrix¶

- In a simple (unweighted) graph, we used a matrix of 0’s and 1’s as an adjacency matrix

- A 1 in row i column j marked an edge between i and j (or from i->j for directed)

- A 0 marked lack of an edge

G1 = complete_graph(4)

locs_x = [1, 2, 3, 2.0]

locs_y = [1.0, 0.7, 1, 0]

labels1 = collect('A':'Z')[1:nv(G1)]

gplot(G1, locs_x, locs_y, nodelabel=labels1)Loading...

A1 = adjacency_matrix(G1)4×4 SparseArrays.SparseMatrixCSC{Int64, Int64} with 12 stored entries:

⋅ 1 1 1

1 ⋅ 1 1

1 1 ⋅ 1

1 1 1 ⋅- We can extend idea of adjacency matrix to include weighted edges

- Suppose nodes A, B, C are friends -- but A-C are best friends

- Also suppose that all of A, B, C consider D an enemy

- To represent this we might say weight of edges is:

A-BandB-C: 1.0A-C: 2.0A-D,B-D,C-D: -1.0

- Here’s the adjacency matrix

A2 = [0 1 2 -1; 1 0 1 -1; 2 1 0 -1; -1 -1 -1.0 0]4×4 Matrix{Float64}:

0.0 1.0 2.0 -1.0

1.0 0.0 1.0 -1.0

2.0 1.0 0.0 -1.0

-1.0 -1.0 -1.0 0.0- And here is how we might visualize this graph (notice the labeled edges)

G2 = SimpleWeightedGraph(A2)

gplot(

G2, locs_x, locs_y,

nodelabel=labels1, edgelabel=weight.(edges(G2)),

)Loading...

Shortest Paths¶

- We talked previously about shortest paths for a Graph

- This was defined as the minimum number of edges needed to move from node n1 to node n2

- When we have a weighted graph things get more interesting...

- Let represent the weight connecting nodes and

- Define the shortest path between n1 and n2 as the path that minimizes for all edges

A->Balong a path

Example¶

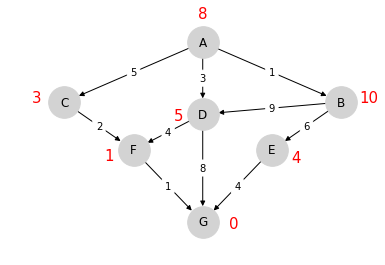

- Consider the following directed graph

A3 = [

0 1 5 3 0 0 0

0 0 0 9 6 0 0

0 0 0 0 0 2 0

0 0 0 0 0 4 8

0 0 0 0 0 0 4

0 0 0 0 0 0 1

0 0 0 0 0 0 0

]

G3 = SimpleWeightedDiGraph(A3)

#plotting details

locs_x_3 = [3, 5, 1, 3, 4, 2, 3.0]

locs_y_3 = [1, 2, 2, 3, 4, 4, 5.0]

labels3 = collect('A':'Z')[1:size(A3, 1)]

gplot(G3, locs_x_3, locs_y_3, nodelabel=labels3, edgelabel=weight.(edges(G3)))Loading...

- We wish to travel from node A to node G at minimum cost

- The shortest path (ignoring weights) is A-D-G

- Taking into account weights we have 3 + 8 = 11

- There are two other paths that lead to lower cost (total of 8)

A-C-F-Ghas cost 5 + 2 + 1 = 8A-D-F-Ghas cost 3 + 4 + 1 = 8

- For this small graph, we could find these paths by hand

- For a larger one, we will need an algorithm...

Shortest path algorithm¶

- Let be the minimum cost-to-go from node to node G

- Suppose that we know for each node , as shown below for our example graph

- Note

- With in hand, the following algorithm will find the cost-minimizing path from to :

- Start with

- From current node move to any node that solves , where is the set of nodes that can be reached from .

- Update notation to set

- Repeat steps 2-3 (making note of which we visit) until

Exercise: Traversing Cost-Minimizing Path¶

- Let’s implement the algorithm above

- Below I have started a function called

traverse_graph - Your task is to complete it until you get that the minimum cost path has a cost of 8 and length(4)

J3 = [8, 10, 3, 5, 4, 1, 0]7-element Vector{Int64}:

8

10

3

5

4

1

0function traverse_graph(

G::SimpleWeightedDiGraph,

J::AbstractArray,

start_node::Int, end_node::Int

)

path = Int[start_node]

cost = 0.0

W = weights(G)

# TODO: step1, initialize v

v = 1 # CHANGE ME

num = 0

while v != end_node && num < nv(G) # prevent infinite loop

num +=1

F_v = neighbors(G, v)

# TODO: step 2, compute costs for all n in F_v

costs = [0 for n in F_v] # CHANGE ME

n = F_v[argmin(costs)]

# TODO: how should we update cost?

cost += 0 # CHANGE ME

push!(path, n)

# TODO: step 3 -- update v

v = v # CHANGE ME

end

path, cost

endtraverse_graph (generic function with 1 method)traverse_graph(G3, J3, 1, 7)([1, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2], 0.0)But what about ¶

- The shortest path algorithm we presented above sounds simple, but assumed we know

- How can we find it?

- If you stare at the following equation long enough, you’ll be convinced that satisfies

- This is known as the Bellman equation

- It is a restriction that must satisfy

- We’ll use this restriction to compute

Computing J: Guess and Iterate¶

- We’ll present the standard algorithm for computing

- This is an iterative method

- Let represent the iteration we are on and be the guess for on iteration

- Algorithm

- Set , and

- Set

- Check if and are equal for all -- if not set and see repeat steps 2-3

- This algorithm converges to (we won’t prove it here...)

Implementation¶

- Let’s now implement the algorithm!

- We’ll walk you through our implementation

cost(W, J, n, v) = W[v, n] + J[n]cost (generic function with 1 method)function compute_J(G::SimpleWeightedDiGraph, dest_node::Int)

N = nv(G)

# step 1. start with zeros

i = 0

Ji = zeros(N)

next_J = zeros(N)

W = weights(G)

done = false

while !done

i += 1

for v in 1:N

if v == dest_node

next_J[v] = 0

continue

end

F_v = neighbors(G, v)

costs = [cost(W, Ji, n, v) for n in F_v]

next_J[v] = minimum(costs)

end

done = all(next_J .≈ Ji)

copy!(Ji, next_J)

end

Ji

endcompute_J (generic function with 1 method)compute_J(G3, 7)7-element Vector{Float64}:

8.0

10.0

3.0

5.0

4.0

1.0

0.0Exercise: Shortest Path¶

- Let’s now combine the two functions to compute a shortest path (and associated cost) for a graph

- Your task is to fill in the function below and get the test to pass

"""

Given a weighted graph `G`, enumerate a shortest path between `start_node` and `end_node`

"""

function shortest_path(G::SimpleWeightedDiGraph, start_node::Int, end_node::Int)

# your code here

endshortest_pathSummary¶

- Weighted graphs allow us to analyze the cost of travsersing paths

- Applied in situations like traffic flows (on physical roads/bridges), resource planning, supply chain, international trade (weights as tarrifs), and more

- Programming skills...

- We built up an algorithm

shortest_pathusing two smaller routines:traverse_graph,compute_J - For each of the 3 functions we were able to write tests to verify code correctness

- Good habit to break a hard problem into smaller sub-problems that can be implemented/tested separately

- Then compose overall routine using functions for sub-problems

- Not all practitioners do this... we’ve seen some scary notebooks and scripts... don’t do that... you know better

- We built up an algorithm